Engaging Students: Essays in Music Pedagogy, vol. 3

Hearing Harmony Holistically: Statistical Learning and Harmonic Dictation

Brian Edward Jarvis, University of Texas–El Paso

I am often troubled by the fact that my sophomore aural-skills students confuse V4/2 with IV during simple harmonic dictation exercises (e.g., I V4/2 I6 V). As the years go by, it gets increasingly difficult for me to imagine what that experience must be like for them. My brain seems to simply suggest the contextual function of the harmony to me with little-to-no conscious effort on my part. That special V4/2 feeling happens before I consciously listen to any voice in particular and I don’t piece it together from actively attending to the bass, then soprano, then inner voices and/or chord quality (as Michael Rogers’s method for harmonic dictation recommends). Gary Karpinski calls this intuitive style of hearing harmony Gestalt listening, while Jay Rahn and James McKay refer to it as the holistic approach to harmonic dictation. Both terms describe an advanced type of hearing that involves identifying chords and chord progressions as complete entities by relying on its overall sound. In this essay I’ll show that students are already hearing harmony holistically and that instructors can add to and take advantage of students’ ability to do so by further nurturing the results of statistical learning. To this end, I’ll outline an improvisational method that transfers a way in which we learn new languages onto hearing harmony in real time.

It’s actually quite easy to prove that our students do already know how to intuitively hear harmonic progressions as a Gestalt even before they begin formal aural-skills training. Try playing a few repetitions of the chord progression I V vi IV, which I will refer to as the “deceptive/plagal progression,” and watch in delight as your students instantly recognize the “song” being played. Of course, due to that progression’s ubiquitous presence in popular music, different songs are likely to occur to them. In order to harness my students’ pre-existing ability to hear harmony holistically and add it to their growing toolbox of detailed listening skills, I’ve taken Rahn & McKay and Karpinski’s implicit challenge to advance our ability to teach hearing harmony holistically or as a Gestalt.

Karpinski describes Gestalt listening as follows:

“After weeks, months, or even years of repeatedly recognizing and labeling particular chords, those chords can become instantly recognizable—in the same Gestalt manner we recognize a well-known face, a familiar voice on the telephone, or the taste of a common spice. Over time, individual chords, harmonic groups—indeed, many musical figures—drop out of the class of stimuli that require intellectual scrutiny in order to be perceived and take a place in a personal pantheon of essentially instantaneously recognizable entities.” (p. 119)

Aside from the labeling aspect, Karpinski’s description explains how our students are able recognize the deceptive/plagal progression so readily and without subjecting it to “intellectual scrutiny.” They have heard the progression countless times over a period of years and their brains have absorbed its regularities through some process of statistical learning allowing them to recognize it with little-to-no conscious effort. Karpinski’s criticism of this technique of harmonic listening seems to be of an essentially practical nature. After all, it may take “weeks, months, or even years of repeatedly recognizing and labeling” before this ability can be acquired. Though Gestalt listening is time-consuming to develop, Karpinski admits that it is an integral aspect of how many expert listeners identify harmony and in my experience it can realistically be taught in a typical aural-skills classroom.

As David Huron demonstrates in Sweet Anticipation, we are better at hearing what we are used to hearing. Our brains derive meaning from chaos by tracking probabilities and creating expectations by performing innumerable calculations upon the data resulting from our vast array of experiences. To take advantage of this we try to improve students’ awareness and accurate identification of all sorts of musical components through a long and circular process of trial and error followed by reevaluation. The problem, from a statistical learning perspective, is that four to six hearings two or three times a week for four semesters is too little, especially considering that new progressions are being played during each class meeting. On the other hand, a song like Miley Cyrus’ “Wrecking Ball” features the deceptive/plagal progression 10 times and Kelly Clarkson’s “Already Gone” features it 14 times and both tracks combined last less than 8 minutes. Even if a student had only averaged hearing one song with this progression every day for a single year (a very low estimate in many cases), then he or she would have heard the progression many thousands of times (e.g., 5110 times if it was Kelly Clarkson’s song). It’s no wonder that they can hear it as a Gestalt. The task, then, is to incorporate a method that allows students to continually improve their ability to hear harmonies and harmonic progressions holistically while allowing for a major increase in repetition in a fraction of the time and still maintaining an actively engaged group.

The experience I try to simulate is like that of someone learning a new language from a native speaker. The native speaks almost constantly while the language learner applies his or her attention fully in an almost desperate effort to make sense out of the flurry of information. There is no expectation that every detail of the native’s message will be captured but the learner will focus on getting a general idea of what the native is saying.

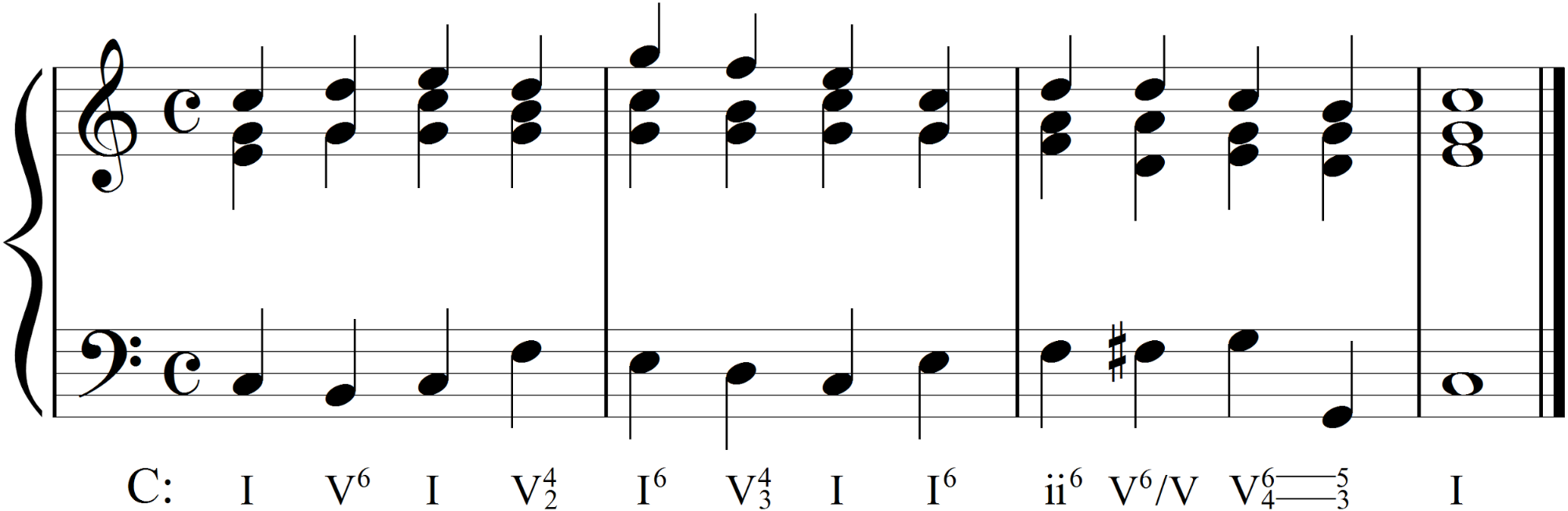

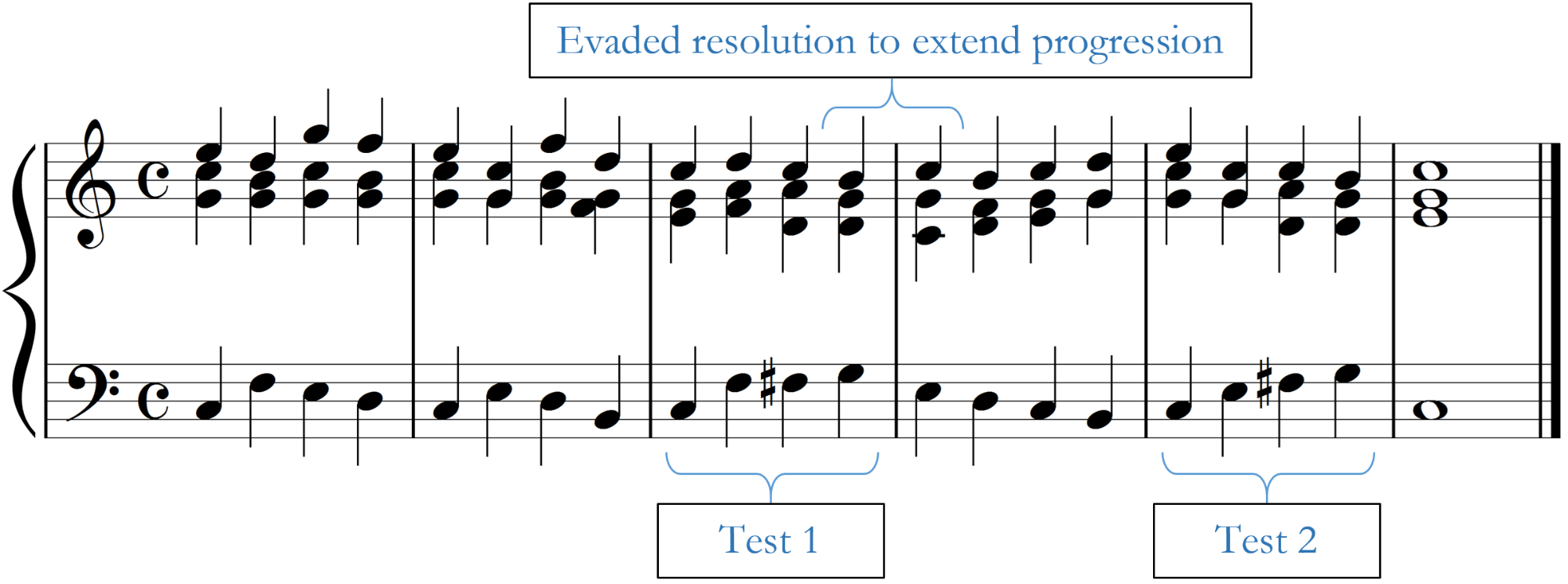

I parallel this language-learning environment by improvising lengthy progressions at the piano, thus immersing them in the “language” of tonal harmony. The activity involves me at the piano with a few precise goals in mind (distinguishing between V4/2 and IV or increasing sensitivity to tonic expansions using a scale degree 1–7–1 bassline, for example) and the students at their desks; pencils and paper are not required. Though the length and difficulty varies by the class level and chosen harmonic idiom, Example 1 demonstrates an idealized outcome likely to arise during a session on dominant tonicization (n.b. evaded cadences and deceptive resolutions are applied liberally to allow progressions to be stretched out and repeated indefinitely).

Example 1. An idealized outcome of an improvised four-measure phrase. To be played slowly and repeated, “reworded” [defined below], and extended as necessary.

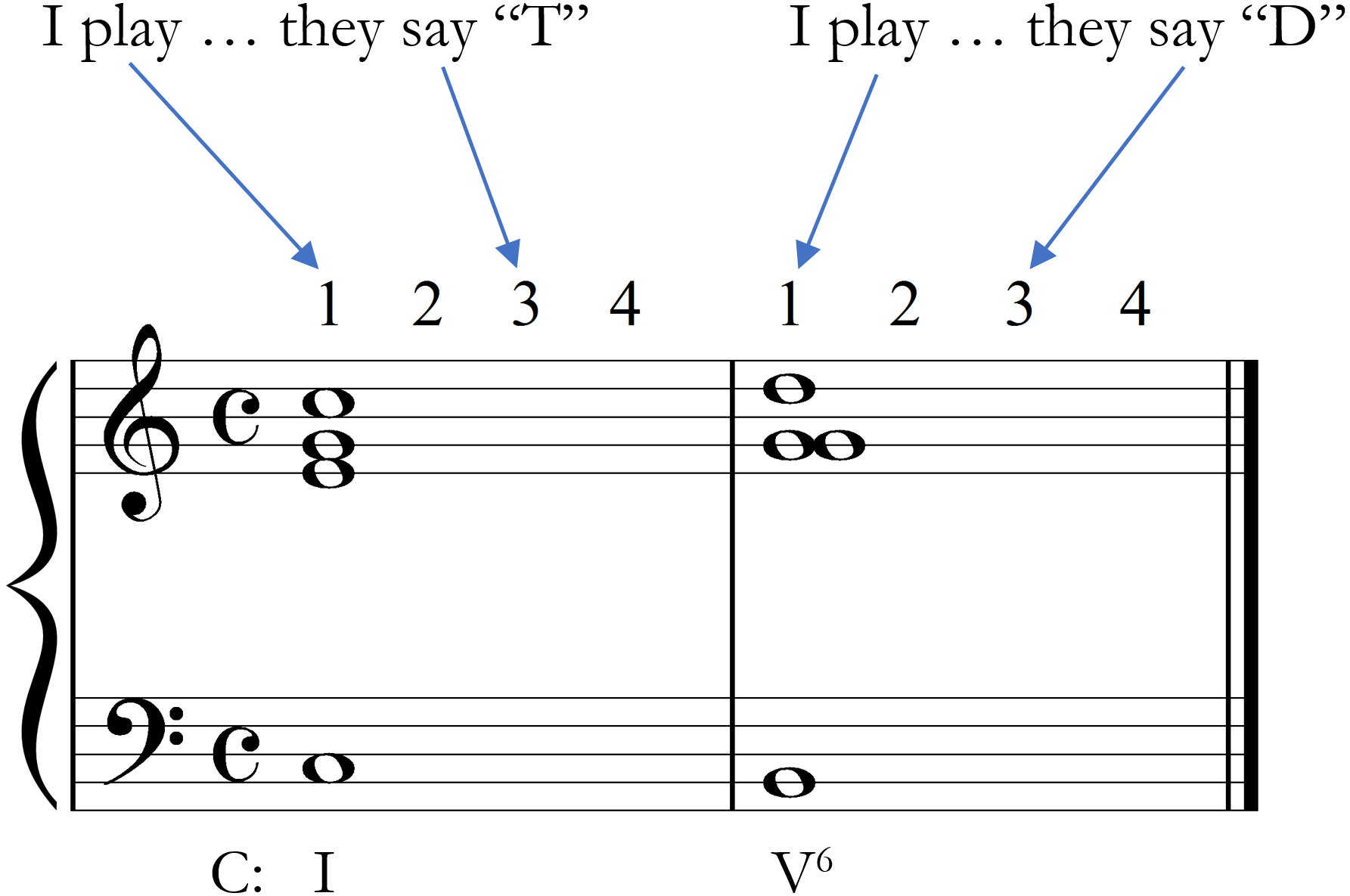

I play a chord on the downbeat of a simple quadruple measure and my students call out the harmonic function on beat three of that same measure as shown in Example 2 (the rhythmic values have been multiplied by four for ease of demonstration).

Example 2. Notation of how my playing is aligned with my students’ responses.

The students speak just the first letter of the chord’s harmonic function, that is, “T” for tonic, “P” for predominant, “D” for dominant, and “C” for all chromatic chords. More specificity in the chromatic category is easily attained by using the first letter of common chromatic chords or groups of chromatic chords (for example, “N” for Neapolitan, “A” for augmented-sixth chords, “M” for modal mixture, and “S” for secondary chords in general). Some students will inevitably know the answer before others, so having them announce it collectively has the dual benefit of not allowing the answer to be revealed early and helps the students to feel secure in offering up an uncertain answer as it won’t stand out like a sore thumb. Additionally, Philip Duker’s clicker method can easily be incorporated to (1) allow for completely anonymous feedback, (2) maximize the accuracy in real-time communication between the students and instructor, and (3) greatly increase the level of specificity of chord labels being announced aloud by the group. The T–P–D–C labeling system is by no means complete, but for the majority of situations it serves its function quite well. Incorporating clickers would also work quite well for cultivating more subtle harmonic distinctions like the difference between the various augmented-sixth chords by offering only a menu of those chords. To continue the language analogy, “vocabulary” quizzes can be achieved by asking the students to respond only when they hear a specific chord (ii°6), harmonic category (dominant), or harmonic technique (tonic expansion).

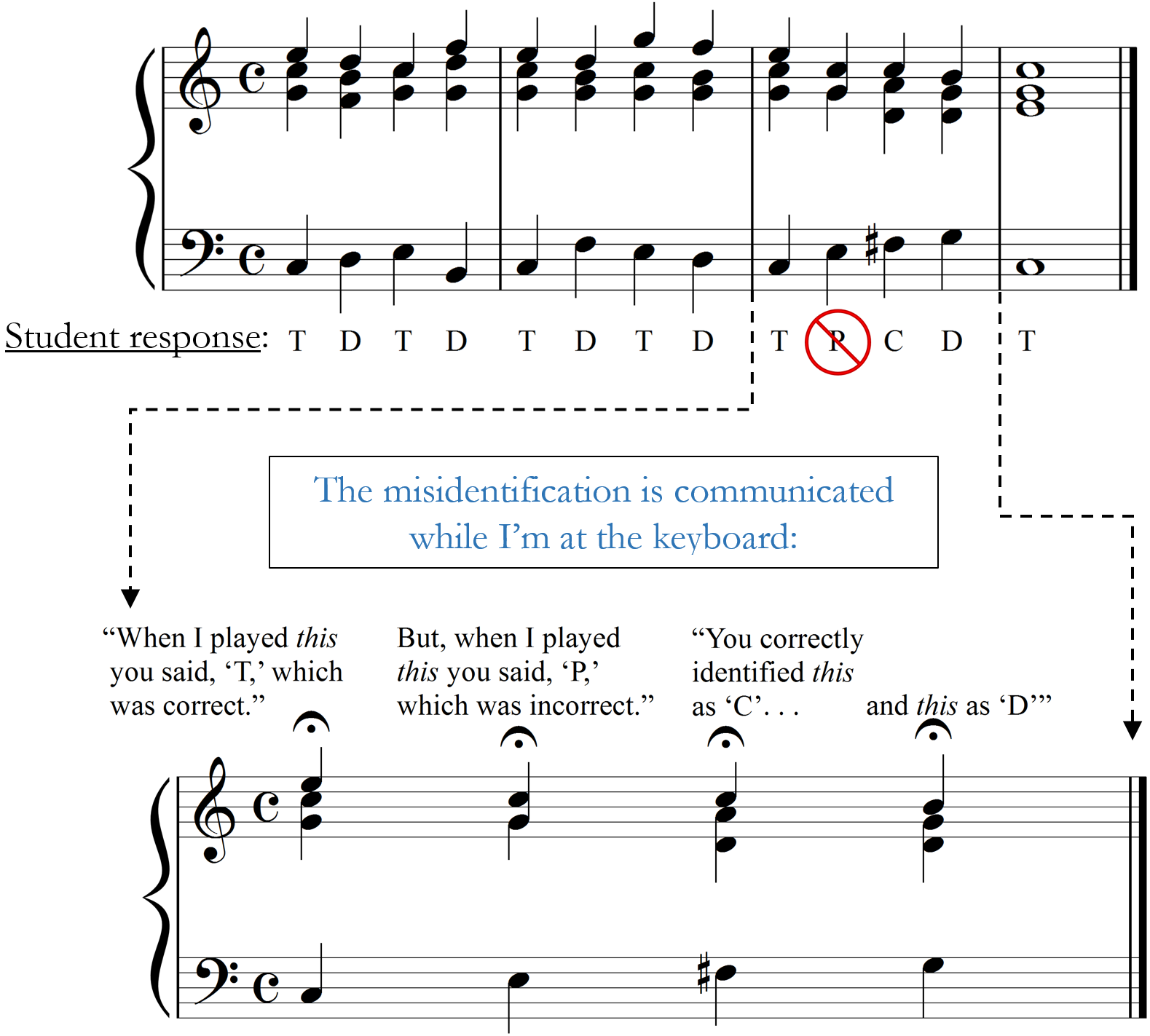

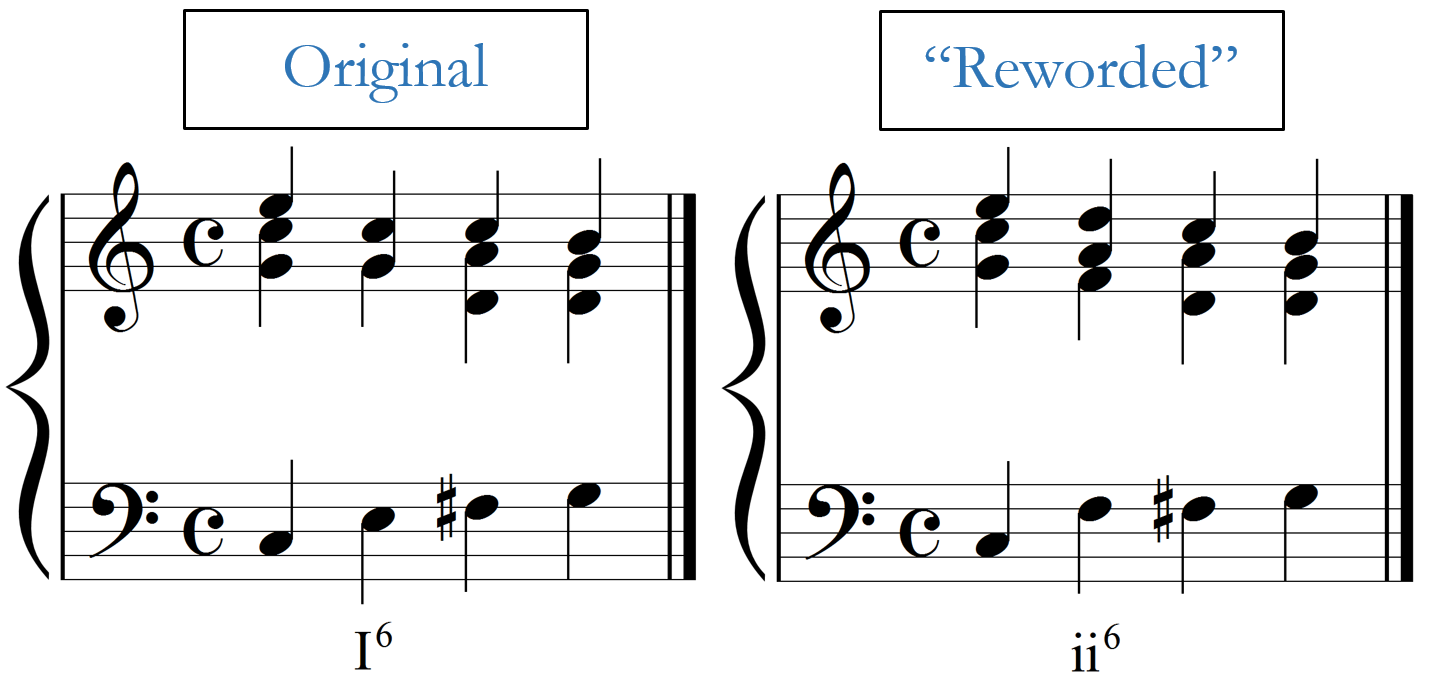

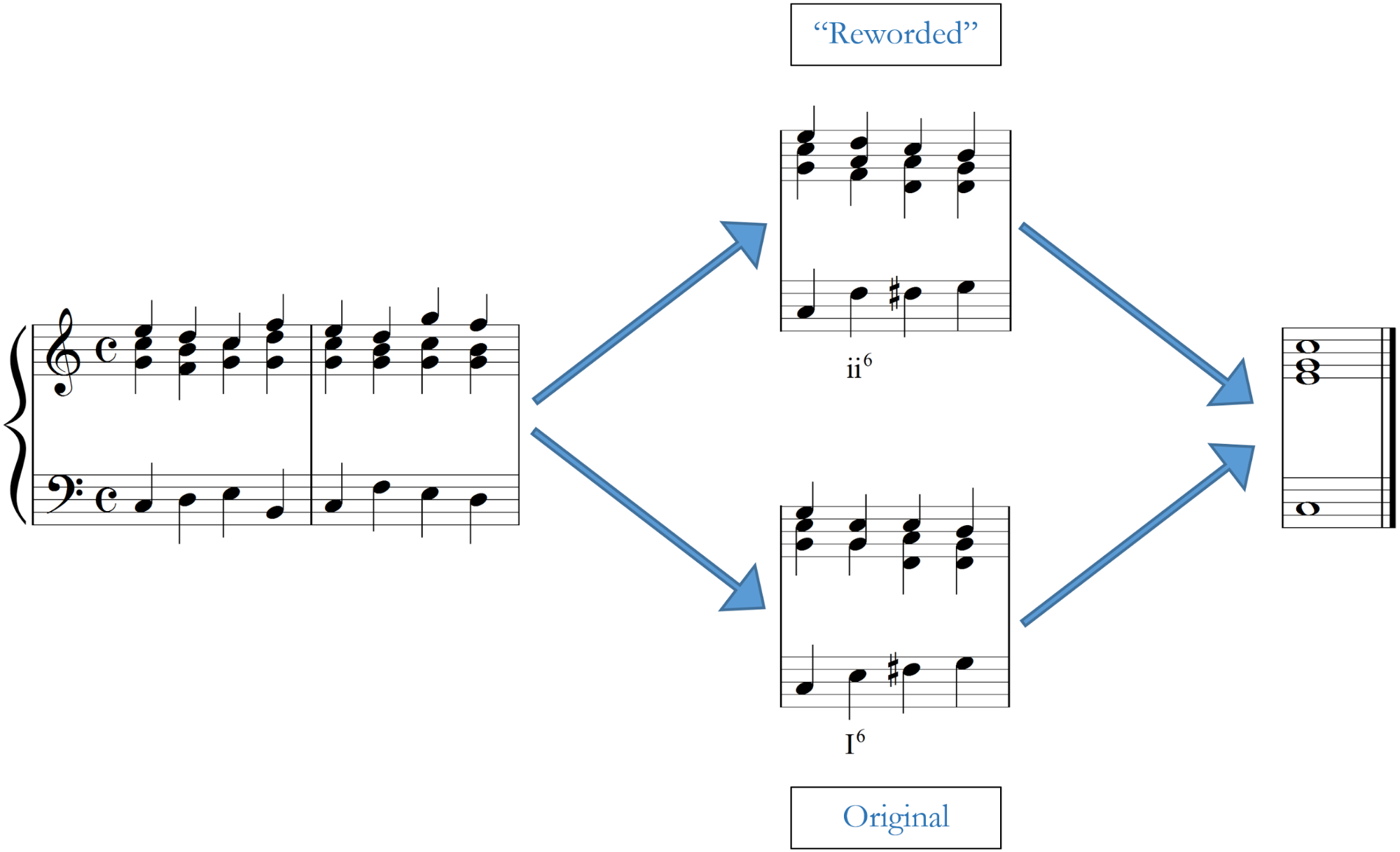

Just as the native speaker in the example above will recognize and respond to the confusion on the learner’s face by repeating and rewording his or her statements, it’s my responsibility to repeat portions by backing up three or four chords to a place where the students exhibited confidence and to “reword” progressions so that the identity of a problem chord becomes obvious. A simple example of “rewording” is often necessary when approaching V6/5/V from I6 especially when the bass leaps up to scale degree 3 from scale degree 1 before moving on to raised scale degree 4. Students will often misidentify I6 as a predominant. Example 3 is a demonstration of the process of “rewording” and repetition I would go through to explore and correct that sort of misidentification.

Example 3. A sample illustration of the rewording-and-repetition process I use to correct misidentifications.

The original harmonic progression:

I “reword” the partial progression with a simple adjustment (in this case, replacing I6 with ii6) and then explore the difference between the two until the students demonstrate competence:

I then return the excerpted progression to its original context and alternate it with the “reworded” version:

Once my students exhibit competence with the original progression, I place the issue into a new context of substantial length, again making sure to repeat, “reword,” and vary as necessary.

Keeping in mind the goal of nurturing statistical learning, I constantly revisit progressions from the past and in the course of a single session I make sure to return to any problematic progressions after moving on to different ones. They are still not writing anything down (though, they can easily do so for quizzing and testing purposes), so each time through the progression the students are actively attempting to consider the chords’ functions anew or reinforcing the connections that led them to the correct answer in the first place. In either case, their brains are sorting through the continuous data and strengthening correct neurological connections or reevaluating incorrect ones. Asking students to consciously track bass scale degrees allows for Roman numerals to be identified in roughly the same manner (i.e., called aloud by the students as in Example 2) and leaves room for the instructor to decide if they wish to spend time on the difference between very similar chords like V6 and V6/5 or to accept both and pursue larger distinctions.

Throughout this activity, it is vital that variations are performed so that students’ brains can start to learn exactly what is and what is not a V4/2, for example. A great way to do this is by varying the melody, key, mode, register, and tempo. If instructors are equipped with, for example, a portable MIDI keyboard and Apple’s GarageBand his or her students would greatly benefit from hearing this exercise in a variety of timbres. Importantly, the progression itself should be varied with chords that are often confused for one another (e.g., IV and ii6 or V6/5/V, vii°7/V, and Ger°3).

This activity is easy to incorporate into existing aural-skills curricula by beginning with simple diatonic progressions and tonic expansions while basic issues are worked out, then gradually adding chromatic chords and sequential patterns into an ever-increasing palette of harmonic options, mirroring the addition of topics in the written theory class. Even advanced topics that are particularly difficult to teach and learn like modulation, chromatic-third relationships, and extended tertian harmonies can also achieve success through this improvisational/conversational approach. Ultimately it is at its most powerful when combined with other techniques like scale-degree identification, the memorization of harmonic idioms, the guide-tone method (such as Daniel Stevens’s Do/Ti test or his numbered types), but it is crucial that special attention be given to Gestalt listening alone in order for the skill itself to develop. The real-time nature of the activity allows Gestalt listening to be developed by forcing students to decide on a chord’s function quickly without relying on other means like retrospective harmonic analysis of multiple melodic lines (a valuable skill, of course, but one that can prevent students from developing holistic hearing if overly relied upon).

In order to capitalize upon the effects of statistical learning that will increase our students’ ability to hear more and more harmonic progressions as a Gestalt, the improvisatory and harmonically immersive process outlined here offers a way to present students with enough repetitions, reevaluations, and varying conditions that will allow them to dramatically increase their ability to hear harmony holistically. A further extension of this method would be to turn the activity over to the students. Doing so allows them to “speak” tonal harmony and is a great way to extend their keyboard training while offering them the opportunity to practice with each other outside of class. As an end-of-semester project they could work towards leading the activity themselves in class (or a simplified version of it).

The most important benefit of the approach outlined in this essay is that it trains students to pair their in-time experience of harmony with their theoretical training in a way that allows them to hear and understand harmony in real music while they listen, an important end goal of the aural-skills training sequence. When incorporated with the types of contextual listening exercises advocated in modern texts like Aural Skills in Context, The Musician’s Guide to Aural Skills, and Strategies and Patterns for Ear Training, students will be well equipped to enter their professional musical lives ready to make the types of connections between experience and intellect that seasoned professionals rely upon regularly for the purposes of understanding and communicating musical information.

This work is copyright ⓒ2015 Brian Jarvis and licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution–ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.</p>