Engaging Students: Essays in Music Pedagogy, vol. 4, Engaging Students Through Jazz

Figured Bass as “Hollowed-Out” Lead-Sheet Chord Symbols

Joon Park, University of Arkansas

Introduction

In many music theory curricula today, the introduction of figured bass usually comes after the discussion of Roman numerals. This article advocates for an earlier introduction of figured bass into the music theory curriculum—before triads and Roman numerals, and alongside intervals, keys, and scales. There are many benefits for introducing figured bass early. First, it prevents students from developing a false historical connection between figured bass and chordal inversion, encouraging students to learn it as a system of notation in its own right, not as a system of notating chordal inversions and suspensions. Second, it frees figured bass from its current limited use. In today’s theory courses, figures are used mostly to indicate chordal inversions and suspensions. This limited usage might cause confusion when figures are used to denote sonorities other than inversions and suspensions (e.g., upper-neighbor figure 5–6–5/3–4–3), or when the style of figuration is different (e.g., 4/2 versus 2 to indicate the third inversion a seventh chord). Third, teaching students to realize figured bass reinforces interval recognition because it involves counting intervals from the bass note within the given diatonic pitch-space, a skill that is more fundamental than identifying Roman numeral functions and chord inversions. By introducing figured bass alongside teaching intervals, the course material can grow exponentially by incorporating historical manuscripts from the baroque era. Finally, as we shall see, figured bass can function as a stepping stone for the realization of lead sheet symbols.

This article proposes a method of realizing figured bass as “hollowed-out” lead sheet symbols by bypassing the identification of chord roots and Roman numerals. By “hollowed-out,” I mean a way of treating a lead-sheet symbol without taking into account its chord quality. For example, treating a G7 chord simply as a combination of two notes: G and F (the 7th above G). Considering figured bass as hollowed-out lead-sheet symbols highlights the connection between the two systems. A lead-sheet symbol combines four components: chord root, chord quality, extension, and an occasional use of slash notation when the chord root is different from the bass note. Figured bass consists of two components that are analogous to the above four: bass pitch and interval(s) above the bass. Both systems contain a reference pitch (a chordal root and a bass note). In addition, a figure’s interval content can be treated similarly to a lead-sheet symbol’s extension because they both involve counting intervals from the reference pitch. By having two equivalent components, a figured bass symbol can work as a mediating step towards the full realization of a lead-sheet symbol. By untethering figured bass from the current use of identifying suspension and chord inversion, and returning to a more historically grounded practice, we can maximize the connection between figured bass and lead-sheet symbols.

Hollowing-Out Lead-Sheet symbols

Figured bass can do more than indicate inversions and suspensions. In its original practical use, a figured bass number simply tells the performer which note above the bass is to be played, notwithstanding a situation when an experienced performer infers what other notes can be added to given figures. By adding figures, this notation can represent many more sonorities than the ones that students would normally encounter in the music theory classroom. Consider, for an extreme example, the famous opening chord from Jean-Féry Rebel’s 1737 Les Eléments (performance). In the bottom staff (Clavecin), the figure reads (from bottom up) 7♯, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6♭, which aptly resonates with the movement’s title “Cahos” (Chaos). To play the opening chord, the performer needs to play seven notes at once. The resulting chord could be written as C♯dim7(11,13)/D, Dm(♯7, 9, 11, ♭13) or could be understood as a polychord comprising Dm and C♯dim7. This example demonstrates that the consideration of chord quality does not have to be an essential step in realizing figured bass.

Figure 1. Jean-Féry Rebel, Les Eléments, mm. 1–4.

This kind of usage demands a set of skills for realizing a figured bass that is different from what is taught in today’s music theory classroom. In fact, many tasks that are commonly associated today with figured bass realization—such as identifying chordal roots, determining inversions, and recognizing Roman numerals—become more important than counting intervals from the bass. By converting chord tones (other than the bass note) into figures, figured bass can help students gain proficiency in interval recognition. Instead of learning chords and inversions together while learning the figured bass system, teaching figured bass first will help students use their knowledge of figures to bolster their understanding of chordal inversions.

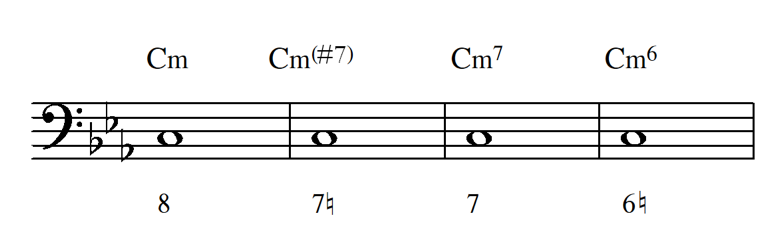

The process of hollowing-out is straightforward. A lead-sheet symbol is treated as the chord root and extensions only, ignoring the chord quality. For example, take a look at the first four bars of “My Funny Valentine” (Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart). We can hollow out the lead-sheet symbols by notating the chord root on the staff and convert the extensions (♯7, 7, and 6) to figured bass numbers. The major seventh above the root in Cm(♯7) becomes a 7♮ figure to counteract the B♭ in the key signature. Similarly, Cm7 becomes 7 taking into account the key signature, and Cm6 become 6♮ to counteract the A♭. An experienced jazz performer would interpret the four lead-sheet symbols as embodying a chromatic descending tetrachord over a C minor triad (C, B♮, B♭, A♮). The figured bass numbers can show this descent more succinctly by adding the figure number 8 at the beginning. At this stage, realizing the figured bass as two-voice counterpoint in oblique motion (one on C the other descending chromatically) would suffice.

Figure 2. The chord progression of the first four bars of “My Funny Valentine.”

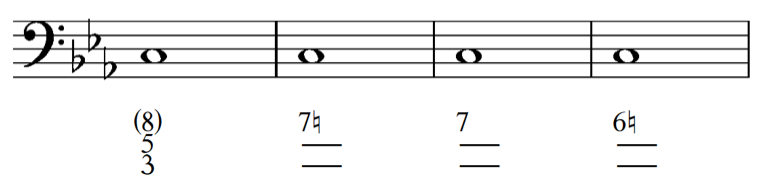

Afterward, the figures can be added to match the full realization of the chord progression (below). This process is, in essence, the conversion of chord tones into numbers. Instead of realizing the lead-sheet symbols on a staff, it realizes them as figures. The consideration of chord quality can follow this stage, as the students can use the figured bass to determine the root of the chord and the scale degree of that root.

Figure 3. Full realization of the lead-sheet symbols into figured bass.

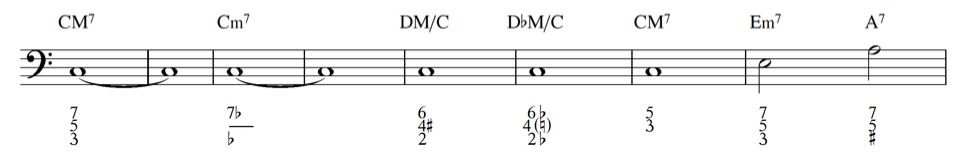

When a lead-sheet symbol has a separate bass note, the figured bass representation can spell out the corresponding chord tones. For example, consider the opening phrase of “On Green Dolphin Street” (Bronisław Kaper). The chord tones of lead-sheet symbols are converted into figured bass numbers, as this example shows. Measures 5 and 6 feature lead-sheet symbols with slash notation to show that the bass note (C) is different from the chord roots (D and D♭). Simply by counting diatonic intervals from the bass and adding appropriate accidentals, we can represent lead-sheet symbols with slash notation as figured bass numbers.

Figure 4. The chord progression of the opening phrase of “On Green Dolphin Street.”

This example also shows that the comprehension of diatonic pitch space can be reinforced by using the same figure to represent different types of intervals. For example, in the key of C major, the same 7/5/3 figure represents different genera of intervals depending on whether the figure is above a C bass (m.1) or above an E bass (m.8). Similar to interval recognition, understanding diatonic pitch space is one of the skills that should be presented early in the curriculum. If a student is not intimately familiar with diatonic intervals, presenting figured bass as a way to indicate inversions would create further confusion and the figures would become a seemingly meaningless sequence of numbers with the arbitrary association of chordal inversions.

I have created sample figured bass conversions of five jazz standards: “Take the ‘A’ Train,” “My Funny Valentine,” “All the Things You Are,” “My Romance,” “On Green Dolphin Street.” (You can download them here.) In these samples, I avoided the use of slashed figures to reinforce the connection between the figures and their referents (i.e., the notes on a staff) by keeping the same accidentals. (Also, considering the fact that it was a common practice in the baroque era to use a slashed 5 figure to denote a diminished 5th interval, teaching slashed figures as raised intervals may lead to confusion should the student choose to pursue historical performance practice.) These samples represent a second stage in the development of the students’ skills as it omits figures 3 and 5 except when they are altered. For example, when a figure 7 is used alone, it is to be understood that diatonic interval of fifth and third is implied.

Using the Method for Baroque Improvisation

Treating figured bass as hollowed-out lead sheet symbols opens up a possibility to bring pedagogical methods for jazz improvisation into the teaching of baroque improvisation. Instead of teaching strict counterpoint rules, Richard Hermann’s and Keith Salley’s research on jazz improvisation works particularly well because their methods do not rely on jazz-specific “chord-scale theory.” (Salley’s article provides a representative sampling of the jazz textbooks that feature the chord-scale theory.) Instead, both theorists approach jazz improvisation according to different structural levels in a manner similar to species counterpoint.

Figured bass, understood as hollowed-out lead sheet symbols, can replace the roles that the chord symbols played in Hermann’s and Salley’s methods. The remainder of this article demonstrates how Hermann’s and Salley’s methods might be implemented to introduce baroque improvisation. The purpose of this demonstration is to show that figured bass realization can be introduced after students learn keys, scales, and intervals, and before Roman numerals.

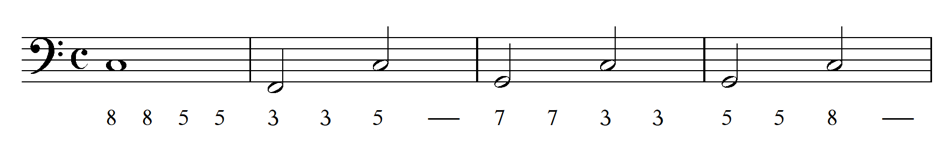

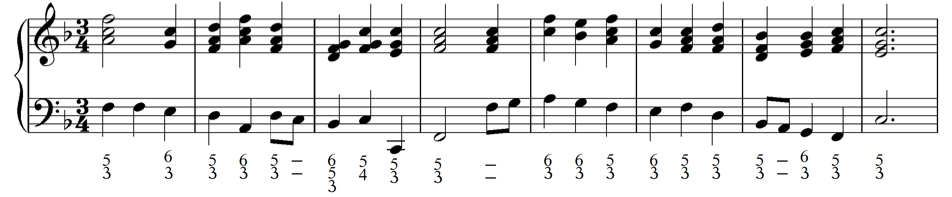

As an introduction, a student can realize a figured bass that outlines a common melody as presented in Figure 5. At this stage, the students can play the bass line with the left hand while playing the implied melody with the right. This is analogous to Hermann’s treatment of the principal bass notes of the harmonies (i.e., the letters of lead sheet symbols) as cantus firmus. The instructor can emphasize that although the numbers may seem to leap at times, due to the moving bass line the students can find a mostly conjunct melody in the right hand. The students can also form pairs and take turns playing the bass lines and realizing the figures.

Figure 5. “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star” in as figured bass, to be realized as two-voice counterpoint.

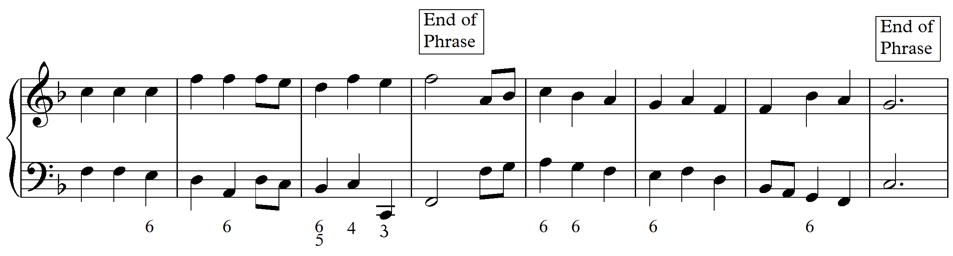

Combined with the knowledge of the major and minor scale, the instructor can proceed with more rigorous improvisation. For this demonstration, I will use an excerpt from Marin Marais’s “Minuet” from Pièces de Viole, Livre V, No. 36 (Figure 6). As a first step, the student can tell what note to play immediately just by counting intervals from the bass note similar to Figure 5. The students can realize the excerpt with full chordal harmony by adding omitted figures. For example, add a third for the written figures 6 or 6/5, add a fifth for figure 4, and add a third and a fifth when there is no figure. The student can write the figures or just add them in their playing without actually writing them down on the score. A possible realization should resemble Figure 7. From this point, the instructor can point out the two cadences (mm.4 and 8) and the Roman numerals associated with them (i.e., I and V).

Figure 6. Marin Marais’s “Minuet” from Pièces de Viole, Livre V, No. 36 (mm. 1–8).

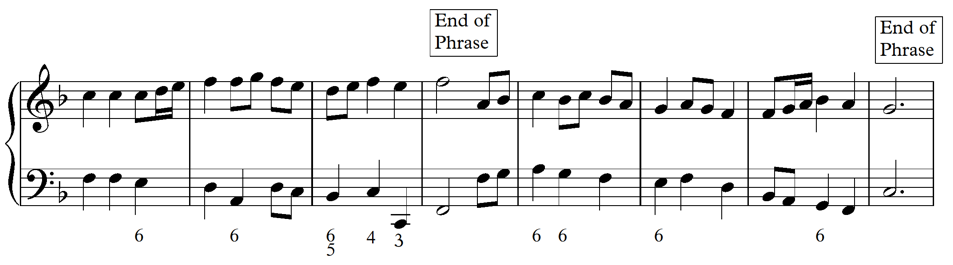

Figure 7. Possible realization of Figure 6.

By now, the students can start constructing a framework for melodic improvisation by choosing one note from the realization for each beat with the goal of creating a smooth melodic line (Figure 8). This step is analogous to Salley’s “species one” which instructs students to create conjunct motion by using chord tones exclusively. This melodic realization can also be implemented as a group activity in which one student plays the bassline and the other plays the melody. An instructor can even let the entire class play their realizations simultaneously. Students can improvise further by adding passing and neighbor tones (Figure 9). From here on, should the instructors choose to continue teaching improvisation, they can draw from Dariusz Terefenko’s method, which begins from a simple one-to-one counterpoint and ends with imitative counterpoint in three voices.

Figure 8. “Species one” realization of Figure 7.

Figure 9. Further improvisation of Figure 8 with passing and neighbor tones.

Conclusion

The method I present in this article aims at building a stronger practical foundation early in the music theory curriculum. This approach complements Open Music Theory, which introduces figured bass early. In particular, my method can precede the “Generating Roman Numerals from a Figured Bass line” chapter that helps introducing Roman numerals for the students who are familiar with figured bass.

There are several advantages of introducing figured bass as early as this article suggests. First, in line with the 2014 CMS Manifesto, this method invites improvisation among students from the beginning. More abstract harmonic understanding will arise from the experience of the improvisation rather than teaching abstract concepts first and looking for suitable examples afterwards. Second, the students are presented with the task of creating a context-sensitive melody with less fear of “breaking the rules,” because whatever mistake the students make while improvising, they can quickly correct it by changing to a pitch represented in the figures. The experience of creating music by improvisation is different from that of writing down the notes on staff paper because, in improvisation, there is no lasting evidence of the error. Also, by framing a figured bass realization as a performance activity, an instructor can assess student work and provide feedback when it is most needed. Third, both jazz and classical music students will find this method useful, albeit for different reasons. For jazz musicians, this method directly helps the recognition of chordal extensions quickly. For classical musicians, this method complements the current notation-based instruction by providing an aural instruction with the direct link to improvisation.

This work is copyright ⓒ2016 Joon Park and licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution–ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.