Engaging Students: Essays in Music Pedagogy, vol. 4, Engaging Students Through Jazz

Multi-Part Group Rhythm Exercises

Rory Stuart, The New School

Introduction

As critical an element as rhythm is in jazz, it is surprising that there are still so few university jazz programs that have courses devoted to rhythm (by contrast, ear training and harmony courses are widespread). The typical rhythmic instruction offered in other classes, whether these are found in a program devoted to jazz or one devoted to classical music or other styles, often focuses solely on sight reading and transcription. Examples from books by people such as Robert Starer and Paul Hindemith, are either sight-read, given to students in advance to prepare outside of class for performance, or performed by the instructor for the students to transcribe. These exercises certainly have value but they fail to address many of the rhythm skills needed to be a truly proficient jazz improviser.

In order to help students develop these skills, I developed an approach to multi-part group exercises that has proven to be very effective, and have used this approach for 24 years in university rhythm classes at The New School for Jazz and Contemporary Music and in clinics and workshops in countries around the world with students who ranged widely in level and background. In these exercises, cyclic rhythmic parts are given to each group to sing or clap; parts may happen simultaneously (not simply hocket style), and the exercises require that students hear the other parts as they sing or clap theirs, and understand where each part falls within the cycle.

Although originally created for jazz students, these exercises are useful for music students regardless of genre. First a comparison: different styles of music and musical training have their strengths and weaknesses, and the strengths of a teaching approach typically address the requirements of a musical style. For example, rock and jazz pianists who have awareness of dynamics listen appreciatively to the touch and control found in good classical pianists, who must thoroughly develop this to address the performance demands of the classical repertoire. A jazz pianist who wants to improve control of dynamics may look to the training techniques of classical pianists and productively adopt some of these techniques.

Similarly, students in many areas of music may benefit from the command of rhythm displayed in the performances of foremost jazz musicians. For jazz to be performed at the highest level, its practitioners must have highly developed rhythmic and improvisational skills. This includes grooves, simultaneous rhythm parts, and time feels of African origins (which can also be found in other music with African roots, such as Afro-Cuban and funk). It also develops deeper levels of listening, spontaneous interaction, and rhythmic improvisation; elements for which jazz is considered exemplary. Although improvisation can be found in a number of musical styles around the world, improvisation in jazz requires a level of interaction that is only possible if one can simultaneously hear and react to multiple fellow instrumentalists, each of whom may be playing a rhythmically different part. Even jazz students may miss the importance of listening and interaction if they learn to play the music through practice with play-along recordings. While musicians in other musical styles do interact some, it is the level of interaction in jazz that is so high and is especially demanding, with every rhythmic and harmonic choice by expert soloists and accompanists instantly influencing what others in the group play next. If one is to effectively “spontaneously compose” as a jazz musician, it is essential to understand one’s part in the context of everything going on around it. Multi-part group exercises build some of the skills required in order to do this.

Jazz has raised the bar in these areas of interaction and listening, and music students, even if they are not planning to specialize in jazz, are increasingly both expecting and expected to develop the skills required to do this (for more, see Robert Levin’s discussion of why classical musicians should learn to improvise). Thus, these exercises may prove useful to teachers of a wide variety of musical styles. Furthermore, jazz pedagogy itself is a young field, and the technique discussed here may be new even to many jazz teachers.

Multi-part group exercises simultaneously accomplish several pedagogic tasks, including: improvement of listening skills, development of rhythmic strength at asserting a part when surrounded by others with different parts, and sensitivity to the groove. As a precursor to playing on instruments, these exercises remove the need to focus on technical issues of instruments, pitch and harmony, thus allowing the student to immediately concentrate on rhythm, listening, feel and groove. What are these exercises? How can you create them? Should they be improvised or pre-composed? In what ways can they be used? Can they be used even with a group of students who vary widely in experience and ability? What are their benefits, advantages, and disadvantages? These are the questions to be addressed in this introduction to multi-part group rhythm exercises.

Method: The Multi-part Group Exercise

There are several effective ways to do a multi-part group exercise; here is a step-by-step description of one of them. For specific examples, see the next section.

The teacher begins by clapping a pulse, giving a countoff, and singing a rhythmic part. As soon as the students can, they mimic the clapping and begin singing the part along with the instructor. At that point, through gestures alone, the teacher indicates to just a small group of the students that they are to continue singing this part. Next, gesturing to another small group of students, the teacher sings a different part and continues repeating it until the students can mimic it and then can sing it on their own. Depending on the number of students and their levels, another two, three, or even four parts can be added, each the responsibility of a small group of the students.

Once everyone is singing a part and the group repeats it a number of times, the teacher counts out loud (to indicate the pulse and remind the students of where their parts fall in the cycle) then, at the end of a cycle, gestures a cutoff to everyone to end their singing. Immediately, the instructor counts off the time for everyone to come back in on their parts. If there is any confusion or uncertainty (e.g. a group doesn’t realize where their part begins or, for example, that it includes a pickup that should be sung during the countoff), the instructor sings along with any group that needs it, clarifying where their part fits. If necessary, this stopping and starting again with a countoff is done several times, until everyone is confident of the correct placement of the parts.

Then, the instructor leads the group in performing the exercise at different, widely varying tempos. It can be especially instructive to see how well students can do the same exercise at a much slower tempo.

Once students are comfortable singing it at different tempos, the instructor returns to the original tempo and begins conducting, indicating to all but one group to sing very quietly, while the selected group sings its part loudly so that everyone can easily hear it; one after another, each group is selected to sing loudly, so that all of the individual parts have been heard very clearly by all students.

At this point, the teacher asks each group to sing a part that was previously given to a different group. Even though all students have certainly had ample opportunity to hear the other parts, it is instructive to see how well they remember them; if necessary, members of one group sing their previous part to another group.

Finally, after each student has sung multiple parts, the class proceeds. The instructor might ask students to notate their original parts and as many other parts as they can remember, and request that a member of each group volunteers to write the part on the board. This can be used as an introduction to and vehicle for class discussion of many rhythmic topics: principles of rhythmic notation, groove, micro-timing, crossrhythms, odd meters, rhythmic superimposition, musical styles.

Example Exercises

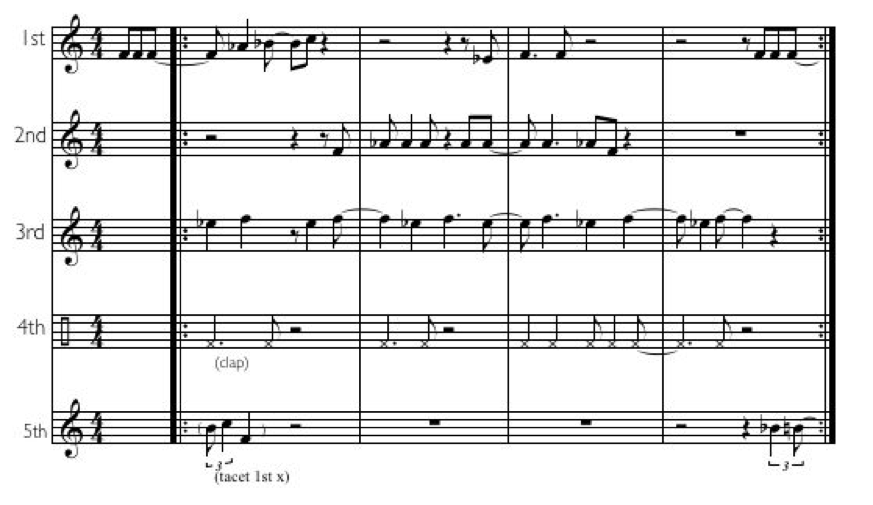

The four examples presented here illustrate some of the qualities of the multi-part exercises. The first is more elementary than what I would typically give my classes, but might be well suited to younger or less experienced students. This is done with straight eighth feel, and all the parts are easy, but they provide some challenges. For example, Groups 1 and 2 have fairly long silences between the moments when they sing; Group 3 has three consecutive bars coming in on the fourth beat before their fourth bar has the feeling of resolution when the land on the first beat; and Group 4 has to feel the syncopation in their last bar:

Figure 1. Four-part example rhythm exercise suited to younger or less experienced students.

The remaining three group exercises have some relatively easy parts and some more difficult parts within the same exercise. Notice that the parts with more space tend to be more challenging to many students. All three include a part with a pickup, and another part that goes over the bar line on the repeat, so that the first notes are tacet the first time through.

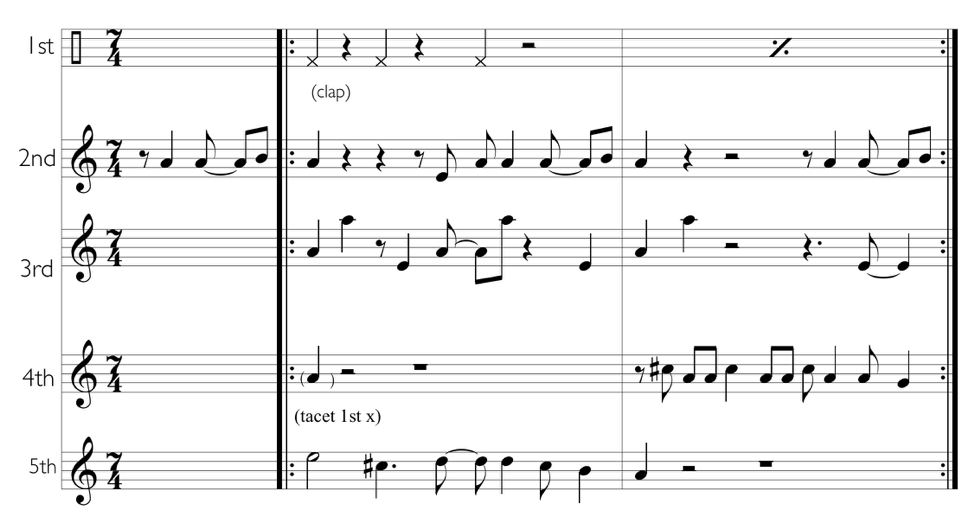

Exercise 2 is done with swing feel, and can be started at a relaxed medium tempo. Group 4 claps the rhythm shown; all other groups clap on beats “2” and “4” as they sing their parts. The parts played by Groups 1 and 4 are quite easy, and Group 2’s is not too difficult. Group 3 sings a 5/8 crossrhythm on 4/4; in the version shown here, they “reset” at the beginning of every four bars, but this could also be given to them so that the 5/8 crossrhythm goes continuously (only synchronizing on the first beat of the first bar with the other groups every five cycles). Group 5’s part is not difficult except that there is so much time spent with rests; it can be used as a good vehicle to show how what sound like quarter note triplets starting on beat “4” can be correctly notated.

Figure 2. Five-part swing feel rhythm exercise with pickup, triplet quarter notes over the bar line, and 5/8 crossrhythm.

Exercise 2 is the most traditional jazz of the examples I give here, and the instructor may want to create a lot of exercises of this type. I include Exercises 3 and 4 so that you can see how multi-part group exercises can be used to teach odd meters.

Exercise 3 is a relatively easy exercise that could be used to introduce students to grooving in 7/4. Although none of the parts are difficult, Group 2 must be able to correctly feel two different places to place pickups that resolve on beat 1, and Group 3 must feel the difference between where the last notes in the first and second bars are placed. As students become more comfortable with 7/4, a subsequent exercise could have them all clap the part shown for Group 1, while they sing their own parts over it.

Figure 3. Five-part rhythm exercise to introduce 7/4.

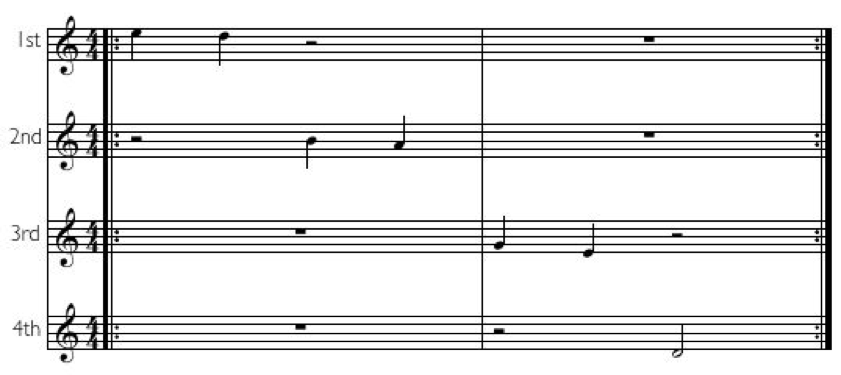

Exercise 4 presents a meter, 15/8, with which many students may be unfamiliar, but gives Groups 1 and 2 very easy parts in this meter. The more advanced students placed in Groups 3 and 4 must be able to feel syncopated sixteenth notes in this meter, with Group 3 singing a rhythmic part without pitches that continues over the bar line at the end of the cycle (thus the first notes are tacet the first time), and Group 4 singing a part that has both a short syncopated pickup and a section that briefly suggests a 7/16 crossrhythm against 15/8.

Figure 4. Four-part rhythm exercise in 15/8 with some challenging parts, for more advanced students.

Improvisation Versus Pre-composition

There are many obvious reasons one might be tempted to pre-compose these group exercises. In doing so, the teacher has something prepared and avoids being put on the spot; goes into the class knowing all the parts will fit together well; has prepared each part so there is no risk of forgetting any of them, even if the students do; has the sense of ease that comes with doing the same thing that has worked in previous semesters. Indeed, doing pre-composed multi-part group exercises can have a lot of value, especially if you create them for a specific group of students you already know.

In spite of this, my enthusiastic recommendation is that, rather than pre-composing them, you create your exercises on the spot, and do them differently every time. There are a number of reasons for this: 1) it allows you to tailor the difficulty of the parts based on the immediate feedback you get from hearing the students; 2) it allows you to arrange parts so that the more advanced students get more challenging parts, and all students get parts whose difficulty is well-suited to their abilities (you can immediately adjust each part, perhaps shift some students to different groups, and get everyone involved in a way that does not go over the heads of the more rhythmically challenged students, yet pushes the more advanced students); 3) it provides for the students a model that implicitly conveys the excitement of improvising (as they observe the teacher making up parts); 4) it increases student awareness of groove: sometimes the parts in the exercise groove strongly together and other times they do not ― it is useful and revealing to have these occasional “failures” (while analytic studies of groove are interesting, students can learn from these exercises in a more intuitive way about what “grooves”); 5) it keeps things exciting for the instructor. This energy can be contagious for the students; in 24 years, I have never tired of making up these exercises or of teaching this subject matter.

It is only fair to acknowledge that this “on-the-spot composition” may come more easily to the instructor who has a background in jazz or related improvisatory styles, but, with practice and experience, I believe it can be developed by any instructor regardless of stylistic background. If you improvise them, your skill at this will improve over time with practice.

Tips on Creating the Parts

There are certain features implicit in the examples. As I have mentioned, the parts can vary in difficulty so that more challenging parts can be given to the more advanced students. Also, there is a desirable balance between parts happening separately versus parts overlapping. Generally, I would neither choose to make an exercise hocket-style (although perhaps this could be useful for young children or total beginners as a warmup exercise):

Figure 5. Hocket-style exercise, with no overlap between parts.

… nor extreme in the degree that parts overlap:

Figure 6. Four-part exercise with too much rhythmic overlap between parts.

Especially if you have a less advanced group of students, or are choosing a meter with which they are not familiar, it helps for the first part you give to feel like it really grounds them in where the beat is, and conveys the beginning of the cycle clearly (see the parts for Group 1 in Exercises 1–4 as examples of this).

I often choose parts that implicitly express certain challenges to the students. Notice that Exercises 2, 3, and 4 all have a part that begins with a pickup; they all have at least one part that begins at the end of the cycle and continues through at least the first beat of the first bar (so those groups are tacet on the first time in the beginning); they all incorporate syncopation in the parts; they all have a crossrhythm part; and they address other specific issues (e.g. quarter note triplets starting on the fourth beat in 4/4, 16th note syncopation in a triple meter).

Skills and Content That Can Be Taught Via Multi-Part Group Exercises

There are some skills and types of content that can be taught via multi-part group exercises where it will be obvious to the students what they are learning. A call and response exercise in 7/4, somewhat different from the type described above, begins with the group learning a two bar 7/4 groove interlude; next the class alternates between each student improvising for two bars and the group singing the interlude; then they progress to alternating four bars of improvising with a four bar version of the interlude. It could then proceed from students singing the exercise to playing the same thing on their instruments. By the end of this, it is obvious to the students that they are becoming more comfortable at both feeling and improvising in the meter. Similarly, students learning a new rhythmic style, a new meter, or a new idea (such as crossrhythms) will immediately realize how they benefit from the exercises, as they will if the exercises are used to practice notation and explain notation principles.

But multi-part group exercises help with other things that are entirely implicit, such as feeling micro-timing, hearing where a part falls within a rhythmic cycle, and being able to change the tempo of a part. The ability to slow down a rhythm, for example, requires feeling exactly how it fits in the time and can be very useful in thinking about how to notate it. Students develop these implicit skills, often without realizing they are learning them through the exercises. Other skills, such as keeping a consistent tempo, learning and remembering a part, and hearing other parts while singing one’s own part, are typically strengthened by these exercises, without any need for discussion. A pointer to students to notice how parts fit together and what does (and does not) work well is sufficient to build groove awareness without a great deal of discussion. A teacher who is improvising these parts should not hesitate to revise any part that does not groove well, and the students get to hear whether the revised part grooves better.

The exercises are a way to introduce a topic that can make the subsequent discussion more interesting and exciting. Have one group of students sing a 5/4 crossrhythm on 4/4, or a 3/4 crossrhythm on 7/4, before speaking about what they are doing. They feel the rhythm, hear how their part fits against the groove, and notate the part (in some cases, struggling to do so); a discussion of what they have just done now makes the topic of crossrhythms (also described in the classical world as “implicit polymeters”) much more compelling than it would have been if introduced through a purely didactic presentation. Similarly, singing an exercise that is easy and feels natural, in which one part has quarter note triplets starting on the fourth beat in 4/4, and then having the students try to notate this, can lead to a fruitful discussion about which beats need to be shown by the notation. Singing the essential rhythms in styles such as guaguancó and maracatu makes it even more interesting for students who can hear recordings of both folkloric and jazz-influenced versions of these styles.

Strengths and Weaknesses of Multi-part Group Exercises

There are many obvious benefits and advantages of using multi-part group exercises in teaching rhythm. If you ever find yourself giving a clinic in another country where the students do not speak your language and the translator provided is struggling, there is no better way I’ve found to connect immediately and directly with the students than to use these exercises. There is a remarkable amount one can teach them in many areas of rhythm without ever speaking a word.

Whether facing a school class with students who vary widely in experience and ability, or teaching a workshop or clinic where one can not know anything in advance about the levels of the students, improvising these multi-part exercises allows remarkable flexibility in creating something that is at just the right level for everyone.

It is easy, and valuable, to integrate these exercises with physical elements, helping students gain a kind of non-analytical “body” understanding of rhythm (“embodied musical cognition”). For example, students can be tasked with stomping their foot at the start of each section of a piece while they sing a crossrhythm, thus gaining familiarity with the interaction of rhythm and song form. Typical exercises include singing pitches, singing percussive sounds, clapping, tapping, finger-snapping, foot tapping, and foot stomps. But, I have had students do these while walking in place or even outside (down a New York City street, producing spectator responses you must see for yourself!). You can easily incorporate even more physical elements, such as those used in South African gumboot or its Brazilian counterpart, American juba, Bavarian schuhplattler, Dalcroze Eurhythmics, and other forms of body percussion.

Finally, there are important areas mentioned above, such as micro-timing and groove, that are not well conveyed through verbal discussion, but very directly communicated through these exercises. The instructor can phrase a part in a certain way, or lay back or push it with respect to the beat, or sing a swing part with more or less uneven eighth notes (or a funk part with more or less swinging 16ths), and the students imitate and learn without any need for discussion.

Perhaps most important, there is no other style of exercise I know that is better for developing a student’s ability to sing or perform one part while listening carefully to other rhythmically distinct parts, an ability truly essential in jazz, but also useful in many other styles of music. Greater rhythmic command and better listening are valuable for the musician in an orchestra, chamber music ensemble, or pop music band, and the exercises can even be used with a group of diverse students with backgrounds in a variety of musical styles.

With respect to the challenges and disadvantages of these exercises, they do put demands on the instructor, who must be able to rather fluently create parts on the spot, remember the parts if the students forget them, and risk occasionally creating an exercise that is not entirely a musical success. In addition, these may not be sufficient as the only exercise used for a class; for example, a group of students who need to improve their rhythmic sight-reading skills should supplement these by sight-singing written rhythmic exercises.

Conclusions

Given that, in the classroom, I always improvise these exercises, it is ironic that, in order to give the reader a better sense of how they work, I had no choice but to compose them. To make these as authentic as possible, I pretended I was singing them spontaneously to students as I created them. You can practice and hear how parts like this sound together, and try making up your own exercises before you do them in front of students, by recording multiple tracks into a program such as Logic Pro, GarageBand, or programs with similar functionality on a PC, such as LMMS.

There are some other ways, in addition to those described here, to do multi-part group rhythm exercises, and you may be able to come up with some that I have not used. But they all share in common language independence, address embodied cognition, and can be used effectively to build rhythmic strength and listening skills. They are a very useful tool for teaching rhythm in the classroom or music clinic setting, even with a group of students whose talents and experience are widely varied. Please feel free to contact the author with any questions or to share your experiences with these exercises.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to express appreciation for the helpful comments and suggestions from reviewers Brian Moseley and Michael McClimon, and from Chris Stover and Garrett Michaelsen. The opportunity to develop experience with these exercises was provided by The New School and by those who graciously have invited me to teach clinics and workshops around the world. Thank you!

This work is copyright ⓒ2015 Rory Stuart and licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution–ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.