Engaging Students: Essays in Music Pedagogy, vol. 5

Inverting Dictation

Daniel B. Stevens, The University of Delaware

“Creation is…a species of perception” —David Lewin

Introduction

In conventional dictation exercises, students notate a musical stimulus. I propose another approach, in which students dictate music that they improvise while listening to a stimulus. I call this approach “inverting dictation” because it shifts students’ focus from the given external stimulus to the sounds that they create in response. The goal is for students to develop the ability to think about, understand, and creatively respond to music using those musical ideas and patterns that they create and audiate while listening. This approach also inverts dictation by flipping cognitive engagement from the bottom to the top of Bloom’s (revised) triangle, such that dictation primarily activates the higher-order skills of musical creation, evaluation, and analysis instead of memory. While students can use analysis and evaluation to achieve success in a normal dictation format (for instance, by comparing a written response to the stimulus to spot errors), such dictations emphasize memorization and reproduction rather than higher-order skills. As a supplement to traditional dictations, inverted dictations help students to connect audiation and notation while interacting creatively with the music they hear.

The pedagogical practice of inverting dictation takes its inspiration from David Lewin’s insight that “creation… is a species of perception.” Musical experience, Lewin contends, involves both the stimulus and the musical behaviors of listeners, including modes of production ranging from virtuosic performances to “everyday acts of ‘musical noodling,’ and a whole spectrum of intermediate activities.” (Lewin, 1986: 377). Lewin’s remark underscores the importance of free creation and improvisation to developing an aural impression and musical understanding. Strong dictation skills involve being able to match music that is heard with patterns that are held and understood in the mind. Further, those “acts of musical noodling” provide listeners a flexible tool for developing these internal patterns. While such noodling might first occur in the voice or on an instrument while listening (or during score study), it could also include a range of written activities, from sketches on paper drawn by children to notated free responses by college students (and to the sophisticated analytical graphs by their professors). Beginning with simple dictation exercises (in which students freely noodle musical notations on paper) can significantly lower the barrier to entry for struggling students and allow instructors to better assess how well students connect creative audiation and notation. When afforded such flexibility, students can adapt the complexity of their notated response to their comfort level, providing a positive indicator of what they can achieve during dictation exercises.

This essay also builds on my inverted approach to teaching music analysis. These pedagogies are supported by the well-established principle that exercising higher cognitive levels while learning produces deep, enduring knowledge of a subject. Just like instructors may invert or “flip” a class to engage students in the classroom with challenging questions and problems (Shafer and Hughes 2013, Duker et al. 2015, Duker et al. 2014), learning and skill-building activities in music classes can be inverted to prioritize creative engagement over rote memorization. Like inverting analysis, inverting dictation leaves room for the student to exercise agency and creativity as a listener, to ask questions (“what bass line might go well with this melody?”), and to develop an understanding of music through a process of experimentation and discovery. Both approaches frame music not primarily as an object “out there” to be dissected and itemized, but rather as a space or experience into which listeners can enter and creatively engage.

Model for Inverting Dictation

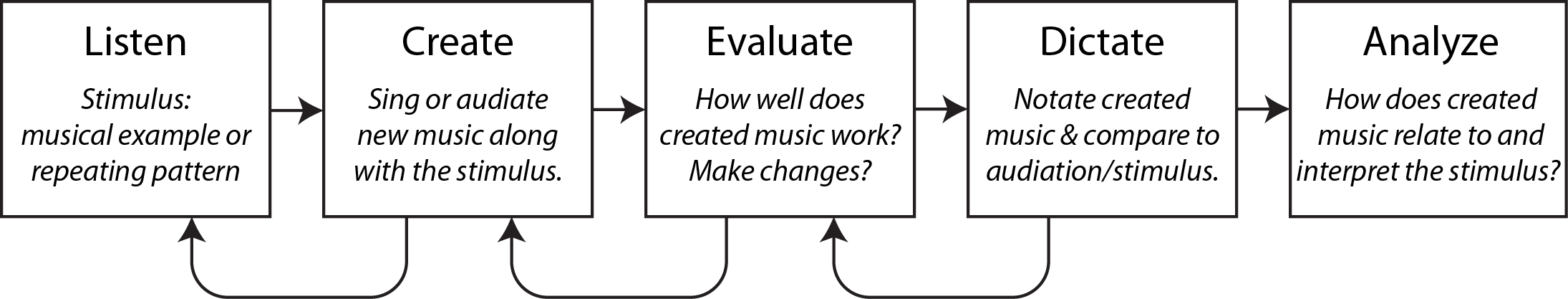

In its simplest form, an inverted dictation involves a student notating a musical response that she or he sings or audiates while (or after) listening to a musical stimulus. Fig. 1 provides a more detailed model that can be used to generate numerous activities beyond the examples provided below. Because inverting dictation assumes that students can generate a variety of musical patterns in response to a stimulus, basic improvisation activities are a helpful and often necessary prerequisite step. (See Schubert 2014, Schubert 2012(a, b, c, d), Rogers and Ottman 2013, Rogers 2008, Michaelson 2014, and Duker and Stevens 2017 for example improvisation exercises.)

Figure 1. Model of Inverted Dictation Activities.

In an inverted dictation, students are encouraged to evaluate and improve their initial musical responses and consider what they reveal about the music that is heard (e.g., location and type of cadence, sequential patterns). Ideally, dictations should include opportunities for iteration, peer feedback, and revision before and during the notation process. After responses are notated, all students (as a class, in groups, or as individuals) sing their notated music along with the original example and consider its accuracy, viability, creativity, any alternative responses, and perhaps even the composer’s original. Including analysis and interpretation helps students tie dictation activities to written theory and other musical activities outside class.

Unlike traditional dictation exercises, in which the texture of the stimulus and response are the same (e.g., a melodic dictation engenders a melodic response), the texture of the notated response in an inverted dictation may be different from the stimulus. For example, students could be instructed to respond to a melodic stimulus by notating an implied bass line, countermelody, rhythmic pattern, guide-tone line, or harmonic arpeggiation. Having the freedom to assign different types of responses has allowed me to use a wide variety of example stimuli, including in-class performances, recordings of classical and popular styles, didactic examples, and small-group improvisations. In what follows, I describe a few such inverted activities—from the more basic to the more advanced—all of which are designed to invite creative engagement, experimentation, risk-taking, critical reflection and analysis, peer feedback, and ultimately a tensile-strong connection between ear and pen.

Inverted Dictation Activities

I first employed an inverted approach to dictation when I began using the Do/Ti Test (Stevens 2016a; see also Stevens 2013), based on the guide-tone method developed by Rahn and McKay (1988). Students apply the Do/Ti Test by singing guide tones with each harmony in a progression, grouping them into “Do chords” and “Ti chords.” Despite the simplicity of the response, guide-tone dictations provide great insight into how students listen and respond to music. More importantly, lowering the complexity of response has made this form of harmonic listening readily applicable to hearing––and grappling with the complexities of––real pieces across a range of styles and genres.

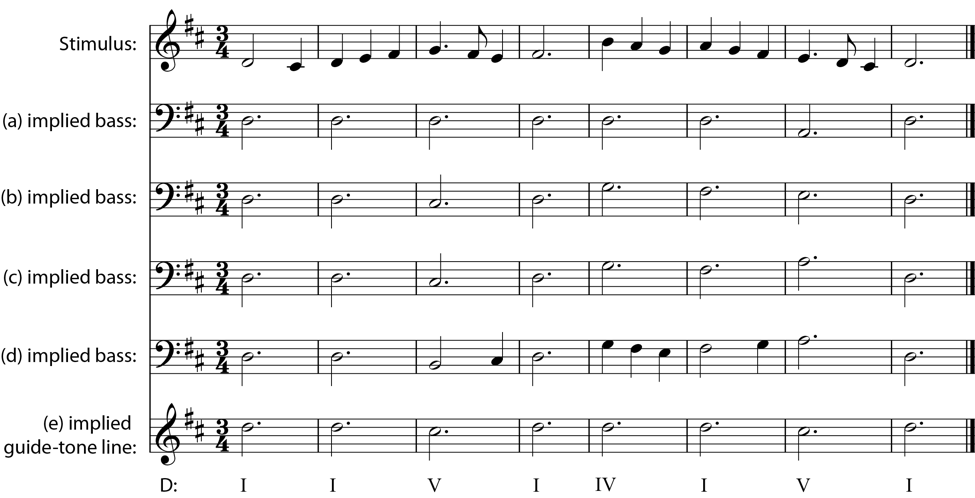

Another inverted approach is for students to sing and notate a melody or countermelody (Root 2016) to a short progression or musical passage, like the melody given in Fig. 2(a). This activity can be completed as a class, with one group of two or three students working together to sing an improvised (counter)melody, another identifying its solfege, a third group notating the suggested countermelody, and everyone discussing the quality and viability of each suggestion. Depending on the length and divisibility of the passage, these roles can be rotated between groups. Dividing the component skills in an inverted dictation between different groups helps model the process that individual students will use when they eventually complete similar dictations on their own. This activity can also be completed in small groups (with individual group members taking on the roles described above). Eventually, each student is expected to generate, audiate, and notate a (counter)melody to a short musical passage.

Fig. 2(b) shows another response type, inspired by materials in Ottmann and Rogers 2013: harmonic singing. Working individually or in small groups, students first use the Do/Ti Test to identify the real or implied harmonic progression of a musical example or given melody. Next, they sing or audiate a harmonic arpeggiation around the guide tones. To increase difficulty and variety, students could be asked to alter their pattern by avoiding specific guide tones (such as the G4 in m. 3) and adding passing tones. After a short period of free improvisation, each student notates the embellished arpeggiation they created and then discusses it with their group members.

Figure 2. Beatles, “I Want to Hold Your Hand,” Refrain, with countermelody and arpeggiation.

Melodic stimuli also provide excellent opportunities for students to dictate new musical lines, such as an implied bass, implied guide-tone line, or another countermelody. The student responses given in Fig. 3(a), (b), and (c) use only dotted-half notes. While simple, the response in Fig. 3(a) shows the level at which the student can audiate and notate responses while listening. Discussion with this student may positively reveal a discomfort with singing a dissonant C# on the downbeat of measure 3 and the intention to establish a cadential dominant. Encouraging this student to take more risks and embrace dissonances might quickly lead to a musically compelling response. While the response in Fig. 3(b) is workable, I would expect that the peer feedback process would alert the student to the suggestion of parallel octaves in the final two measures. Fig. 3(c) is improved both by the congruence between melodic sequence and bass descent and the inclusion of a stronger cadential gesture. Later in the semester, students are expected to include several measures of rhythmic variety and at least one measure of parallel 3rds or 6ths, as in Fig. 3(d). Fig. 3(e) applies the guide-tone method to identify likely chord functions. To reiterate, in each of these exercises, students are only expected to notate the music that that they conceive while listening. In no exercise are they provided the stimulus in notated form. When students try to hack the exercise by dictating the melody and “figuring out” a bass, I encourage them to think in sound as they listen; in many cases, these students claim to develop ideas that hadn’t occurred to them when generating music on paper. Depending on the length and difficulty of the stimulus (or of the expected response), I may well give between four and eight playings of the stimulus to allow students time to improvise and notate their response, and then check their work by silently singing it along with the given music.

Figure 3. Dictation of an implied bass and guide-tone line to a given melody.

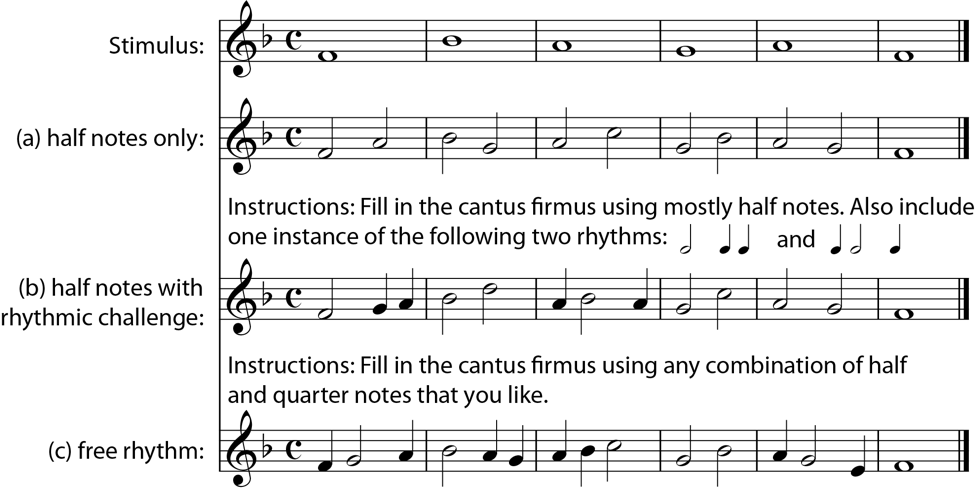

Another approach to inverted melodic dictation is to play a cantus-firmus style melody for students, who respond by adding half notes, as in Fig. 4(a). In later units, students can incorporate one or two unique rhythmic cells, as shown in Fig. 4(b). By semester’s end, students may use whatever combination of quarter and half notes they wish, as in Fig. 4(c). Given the simplicity of the stimulus, I encourage students to sing their improvised melody to a partner before writing anything down. After both students have finished dictating their finished improvisation, they can help each other identify discrepancies between what was sung and notated.

Figure 4. Dictation of an improvised melody based on a given cantus firmus.

The next two examples are slightly more advanced due to the increased level of planning required and their dependence on student feedback. Accordingly, I recommend applying these strategies once instructors and students are accustomed to the method and goals of inverting dictation. Each of the activities below maximizes (1) the evaluation period during which students iterate on prior responses and (2) the amount of peer feedback and discussion that occurs during the process.

In “what comes next?” exercises, instructors give groups of two or three students (let’s call them players: P1, P2, and P3) a short excerpt of music, such as the first two measures of Schubert’s “Heidenröslein,” shown in Fig. 5, and ask them to generate possible two-measure continuations.

Figure 5. Schubert, “Heidenröslein,” D. 257, mm. 1-2 (melody).

Only P1 is allowed to look at the excerpt. P1 begins by singing it in solfege while all three players conduct. In turn, P2 and P3 each respond to the stimulus by singing on a neutral syllable (“la”) music that they think might come next. This cycle repeats several times until P2 and P3 have created a unique, hopefully satisfying response. Next, P2 and P3 teach their final responses to the other two players in the group, who sing them back in solfege and provide suggestions for modification or improvement. Once all players have learned both responses, the players pause to notate the responses, check their work with the others by singing all the melodies, and make corrections as necessary. Finally, both responses are compared to Schubert’s own continuation, provided by the teacher at the end of the process, and students analyze the original to find similarities and differences between their continuations and the composer’s.

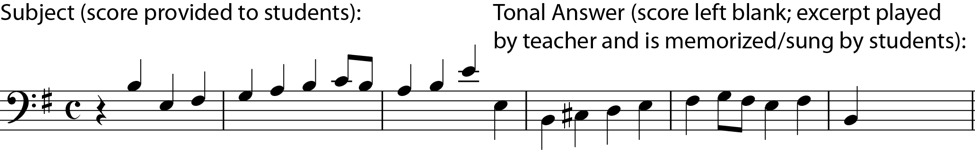

In “what goes with?” exercises, instructors give small groups a musical excerpt and ask them to improvise and notate one or more additional lines, similar to the speculative pre-analytical work described in Inverting Analysis (Stevens 2015). The process of creating and notating a musical response is similar to that described in a “what comes next?” activity. Simple ground bass patterns and fugue subjects, such as E minor subject from Handel’s collection of figured-bass exercises given in Fig. 6, provide material for intermediate and advanced students to generate a response. Over a ground bass, students may be asked to improvise successively more complex upper lines. In response to a fugue subject, they may attempt to identify by ear the answer (played by the teacher) and improvise several possible countersubjects.

Figure 6. Handel, Fugue in E minor: subject and answer.

The emphasis in these activities need not be on finding the “best” or “correct” solution. Rather, each group member is expected to notate each of the possibilities the group considers as viable options. Students then reflect within the group, as a class, or later in a written journal about the relative merits of each solution. In these advanced approaches, the instructor does not play an active role by providing repeated playings of a stimulus or guiding students to the “right answer.” Rather, students are given a structured challenge that engages them creatively and critically while fostering meaningful peer-to-peer dialogue.

Assessing Inverted Dictations

Inverted dictations allow students to align the complexity of their response with the level at which they can coordinate creative audiation and notation, freeing students to exercise creativity as they listen. Accordingly, assessments can focus on a range of learning outcomes, including a student’s ability to:

- notate a creative response that fits a given musical stimulus;

- meet specific compositional challenges;

- sing notated music along with a stimulus;

- evaluate the quality and accuracy of the student’s (or peer’s) response;

- provide meaningful peer feedback;

- analyze and compare stimulus and response;

- make accurate analytical and interpretive observations about the stimulus.

Casting such a wide net is motivated by an intention to create assessments that (1) allow students to show their best work and to clarify where improvement is needed; (2) build student confidence and place authentic success within their reach; and (3) allow teachers to measure student growth in a way that can lead to meaningful, positive course and curricular development.

In my classes, assessment occurs in stages throughout the learning process, and it is open to student and peer input. As often as possible, students are allowed to explain the music they created and its relationship to the stimulus. Such explanations often involve as much singing as verbal communication. In most activities, assessment begins when students receive feedback from their peers. Even at these beginning stages, students should be encouraged to evaluate each other’s work with reference to course standards. While assessing inverted dictations can take instructors longer to administer and grade than a standard one-hour dictation exam, it is possible to cut down significantly on time by observing and scoring student work in class. Because assessments practices are tailored to each student, some students might be able to demonstrate in class that specific outcomes are being met and surpassed. Other students might benefit from one-on-one appointments that allow for varied approaches and dialogue about strengths and weaknesses.

Inverting dictation works well with standards-based grading (Duker et al. 2015). Rather than assign a single overall score or percentage to an inverted dictation, instructors identify a collection of specific learning outcomes covered by that exercise and assign separate scores for each outcome. At the University of Delaware, we use a four-point rubric to assess course learning objectives, with scores “3” and “4” being passing, and scores “1” and “2” showing that progress is needed. For each activity, we establish unit-specific benchmarks that students must meet to receive passing credit. Capstone goals challenge students to exercise creativity and work toward later units’ standards. Throughout the semester, students collect several scores for each outcome and use them to identify areas where improvement is needed. The syllabus includes a chart that translates final semester averages into letter grades.

Final Thoughts

If music was only an external object and listening an act of passive reception, teachers might rightly consider traditional dictations (especially those that accurately represent a given stimulus) to be complete musical statements. Inverting dictation assumes that there is more music worth dictating in every musical experience than those sounds that are received. By inviting students to become vulnerable and add their voices to the musical experience, inverting dictation enables them to develop strong aural skills while respecting their human fragility and the musical value of their creative responses to sound. As students grow comfortable scaling their responses according to their individual abilities in a variety of musical contexts, they can learn how to apply their aural skills across every facet of their musical lives.

This work is copyright ⓒ2017 Daniel B. Stevens and licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.